John Lennon was belting it out on my Sirius radio this morning: “All we are saying….is Give Peace a Chance.” (Enjoy a moment of humming that tune!)

It felt synchronous because I was returning to a school that spoke commitment to peace and unity at every turn. Community Montessori School in Jackson, Tennessee is a public Montessori school with a 30-year history. “How do they do it,” I wondered. I couldn’t wait to sit down with their head of school to find out.

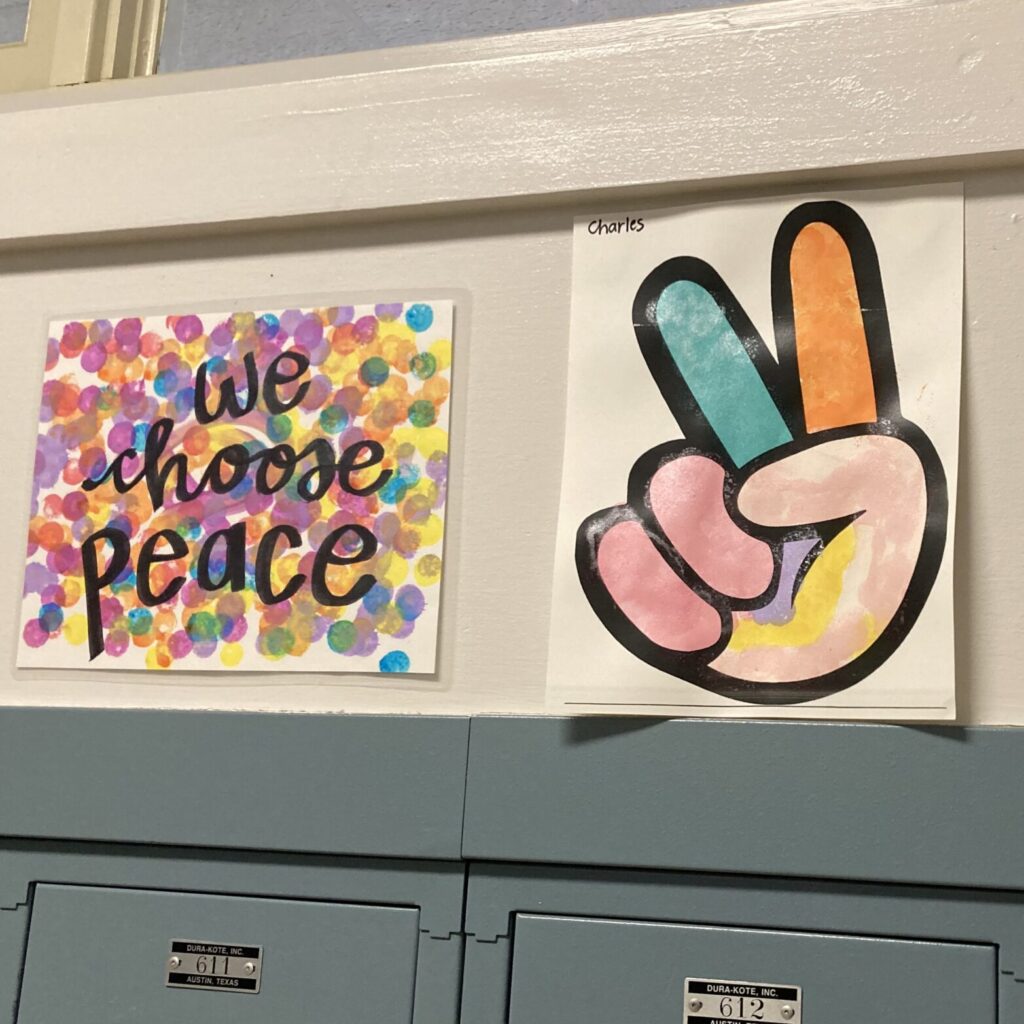

In so many words, what she told me was that they did their best to live up to Maria Montessori’s words of “Follow the Child” by encouraging success and confidence at every turn. One way they’ve done this is by surrounding themselves with uplifting messages that remind the community to remember we’re all connected.

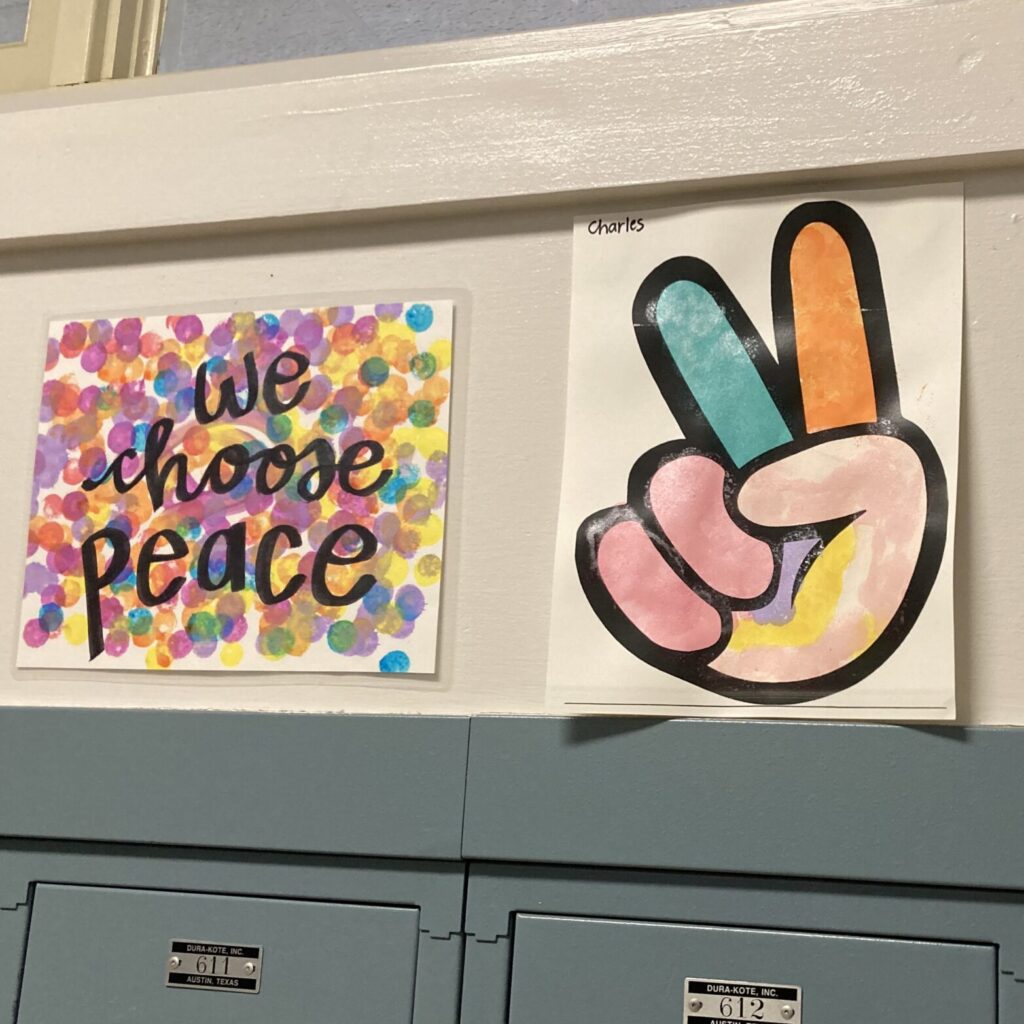

Messages of peaceful collaboration abound. The school’s identification sign is a pair of angel wings filled with symbols of peace. Not only a photo-op invitation, but a feeling of soaring into a peaceful space each day.

A commitment to collaboration continues inside the foyer: a giant globe surrounded by cutouts of little people holding hands and a Montessori quote to clearly communicate bringing up the children to lead into the future. The series of materials in the cases below makes sure the visitor knows this is a school committed to the Montessori vision of Education and Peace.

There are visible signs of inclusion, too. For example, each classroom offered a small table outside the entry for freely choosing a lunch option, often with a gentle connection to the natural world, a reminder that we are part of nature and nature is part of us.

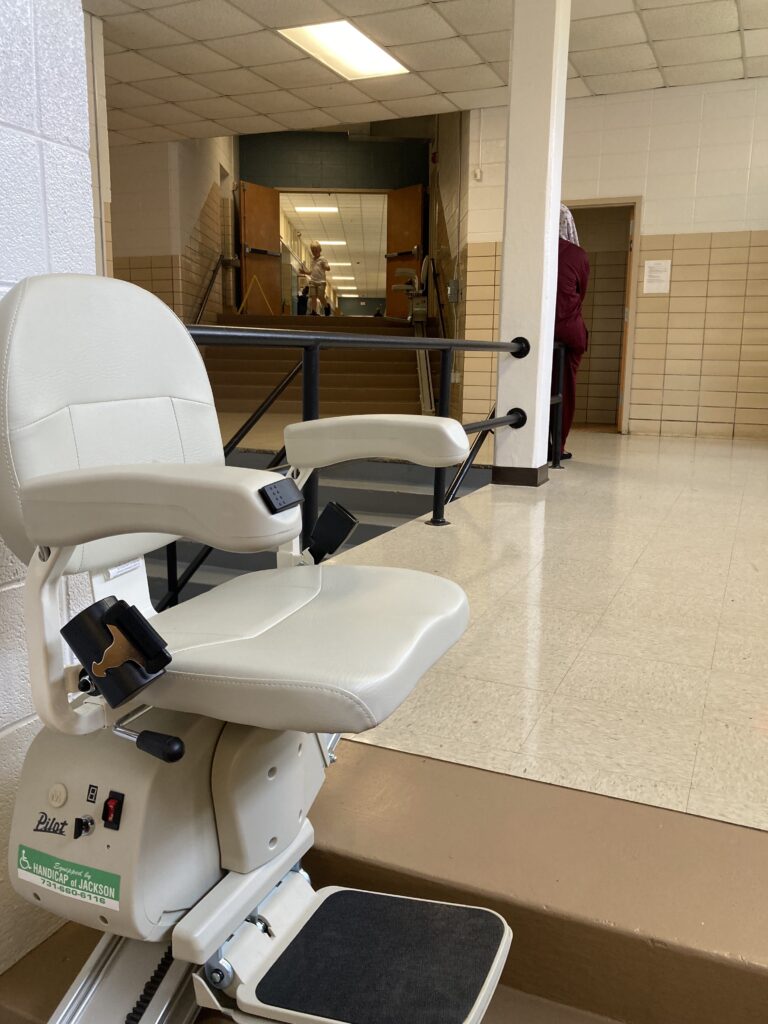

The chair lift at the double stairs spoke volumes about making it possible for everyone to participate with independence and dignity.

Everywhere I looked within the uncluttered spaces were symbols to remind individuals to focus on living in peace. These symbols serve as constant reminders to consciously navigate the world with love, compassion, and understanding, making a powerful impact on shaping behaviors and attitudes…on cultivating a peaceful mindset.

At Community Montessori, these messages are contributing to a harmonious and peaceful society within the school walls, and ultimately out into that giant world beyond them, by creating peace within each person who learns and grows here.

We can each “give peace a chance” by surrounding ourselves

with reminders to practice peace throughout our days.

How will you “give peace a chance” today?