Finding One’s Voice…At Any Age!

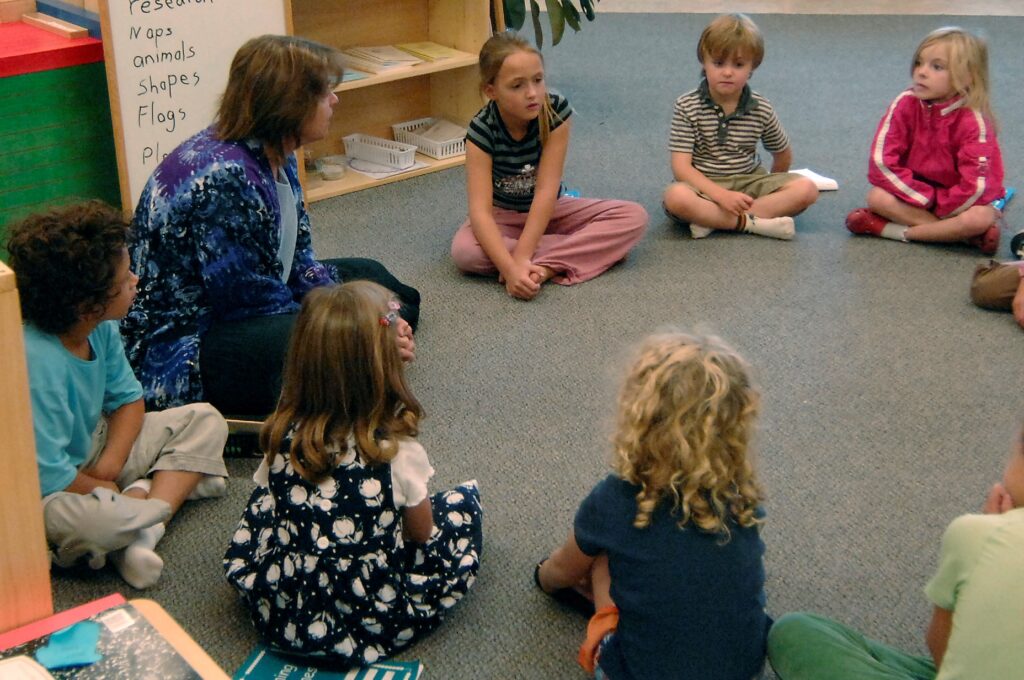

“We must give him the means and encourage him. ‘Courage, my dear, courage!” Maria Montessori – The 1946 London Lectures It was often a topic of conversation amongst my Montessori colleagues: at least part of the “means and encouragement” was to help the child find their voice. This included learning to speak in front of …