“ ‘Courage, my dear, courage! … Go on triumphantly. I am here to help you.’ This kind of encouragement is instinctive in those who love children. ”

Maria Montessori, The 1946 London Lectures, p. 131

A lot of Dr. Montessori’s writings, in fact most of them, focus on the potential of the child…a potential that many adults have trouble seeing and believing. How many of us are driven by a need to “make sure” that the child accomplishes, learns, or demonstrates some bit of wisdom: tying shoes, reading, or fixing a snack independently?

When we adults are driven by our own agendas, what do we do; what actions do we take with the children on a day-to-day basis? Many times what we do is try to take control of the situation; to make sure that all the bases are being covered. For example, If I’m concerned a child isn’t learning to read fast enough, I might make practicing flashcards a daily requirement. I might prod or coax a child through a book they “should” be able to read, asking them to sound out a word, to recognize a sight word, or try to read a complete sentence. I might constantly remind the child to pick up a book and give it a try. Sound familiar?

Letting go of our fear response

While desire can impact our actions in a variety of ways, one thing is certain: if we are taking action that pushes or coerces the child into an activity they resist, then we are not trusting the child. That lack of trust could come from some fear of failure, a negative assessment of the child’s abilities, or a worry that the student won’t meet some benchmark or answer a question correctly on a high-stakes test. It might simply come from a lack of faith that the child really wants to be successful or competent.

In The Absorbent Mind, Dr. Montessori tells us, “The teacher, when she begins work in our schools, must have a kind of faith that the child will reveal himself through work.” (P. 252)

But how do we develop the discipline, the courage and the security in our method to find that faith, to get the children to “success” as reflected in this well-known quote: “The greatest sign of success for a teacher is to be able to say, “The children are now working as if I did not exist.” The Absorbent Mind by Maria Montessori, Ch. 27, (p. 283), 1949.

The teacher, when she begins work in our schools, must have a kind of faith that the child will reveal himself through work. She must free herself from all preconceived ideas concerning the levels at which the children may be.

Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, p. 252

The answer lies right in that “faith” quote…”through work.” In fact, Dr. M gives us even more instruction if we continue the quote through the next sentence: “She must free herself from all preconceived ideas concerning the levels at which the children may be.”

Guiding Principles for Building Trust

In thinking about the practical application of trust-building in my classrooms over the years, I maintained a few guiding principles. Here they are, in brief.

- Know yourself and your students…deeply. Then use that awareness to inspire curiosity, by cultivating your own sense of wonder and awe and sharing it with the children.

- Observe…while keeping in mind that the activity chosen by the student may seem aimless on the outside, but may be providing a great service in preparing the student for a future endeavor. Observe with curiosity, instead of assessment or judgment.

- Engage the lively elementary imagination. Use movement, art, music, poetry, and construction to excite their creative juices. Play!

- Create regular opportunities for children to share their discoveries with their peers and their parents through visual, verbal and written expressions. Daily or weekly in-class opportunities build a “learning” community in which students get excited to be leaders and teachers.

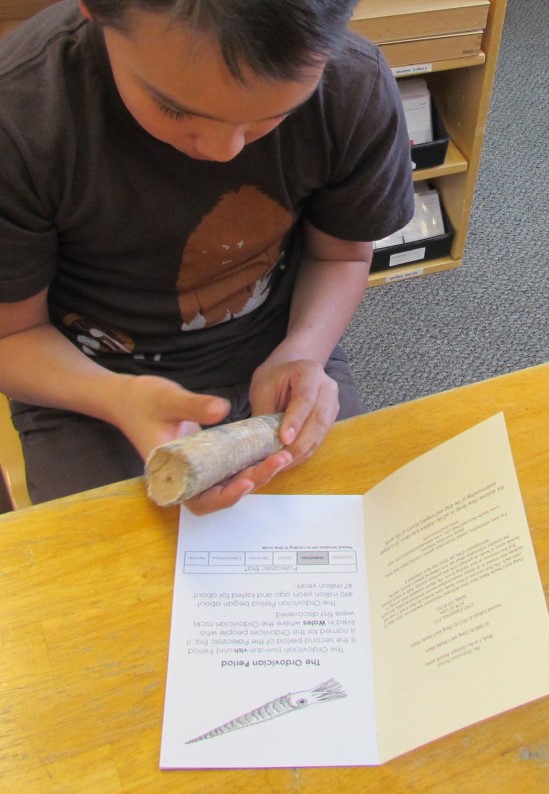

5. Embed skill-developing activities into the cultural studies where they will be perceived as purposeful in mastering the subject of interest. There are so many ways this can be accomplished. For example, when you offer subject-related vocabulary, make note of the word construction (ex: “in-conceiv-able” would allow a discussion of roots and affixes.) There’s no place this works better than in your timeline work: Paleontology, Precambrian, Neozoic…so many! Another timeline example: all sorts of math operations around the study of geologic periods, even having the students make their own to see if they can stump their classmates.

6. Provide lots of “practical life learning” to connect to the natural world while developing confidence and competence. For example, attach a micro business to botany that would allow application of long-term planning, prediction, budgeting, sales, promotion, and all the reading, writing, and calculating associated with it.

Introduce, Stand Back, and Take it ALL in!

Whenever I shared some new theme or subject with a story, a possibility, or an opportunity to discover, design, and share, my students rarely responded in any way that was less than amazing.

Of course, there were those students whose hesitations required some extra support or effort on my part, but the rewards were totally worth it! Watching my elementary students take leadership and teaching roles with their peers and their parents never failed to raise them up, bring them confidence, and spur them on to the next project that would move the needle just a little closer to mastery.

Even when the struggles were big and scary, like dyslexia or dysgraphia, or the fragile self-confidence that caused procrastination or flat-out refusal, the desire to participate with the group, to find their own unique way of joining in, usually won out over time, until even the most challenged found their way to building the skills that would take them into adolescence and adulthood with a growing “can do” attitude.

It was sometimes after years of work, when I sent them on to the next level or got to witness their success through the years, that I knew I was seeing Dr. Montessori’s teachings in action. Yes, I had to exercise a great deal of faith during my early years. I had to rely on what often seemed like tiny, tiny glimmers of the potential held within the child, but now that I can look back with the gift of 30 years and dozens of students, I know that the faith I was able to muster was not in vain.

“These things may seem useless to us, but the child is preparing himself and preparing the coordination of his movements. One consequence of this is that he wants to climb.”

Maria Montessori, The 1946 London Lectures, p. 124