“…when the cycle is completed…refreshed and satisfied, he experiences the higher social impulses…”

-Dr. Maria Montessori, The Advanced Montessori Method – I (1918/1991) pg. 76

Is the 3-hour work cycle challenging you or your students? From time management to task management, sorting out how to effectively get through the 3-hour work cycle can be a SUPER challenge! When I first started teaching, I couldn’t quite imagine orchestrating the work cycle so my students stayed on task, while I accomplished the lessons that would help all of us meet the goals I had for the students.

That italicized “I” is on purpose…my goals for them! I didn’t realize, when I was a new Montessori guide, that it was their goals for themselves that truly mattered. My work was to prepare the circumstances that would hold the students securely while they discovered what those goals really were.

Focus on Order

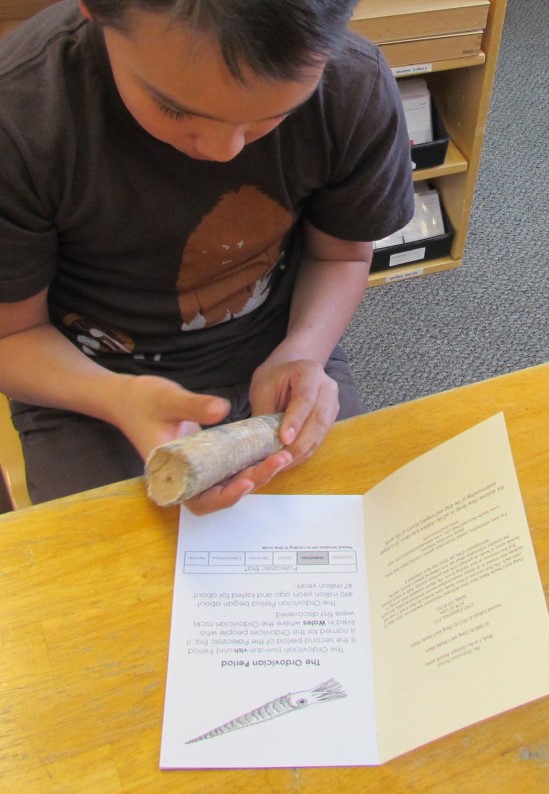

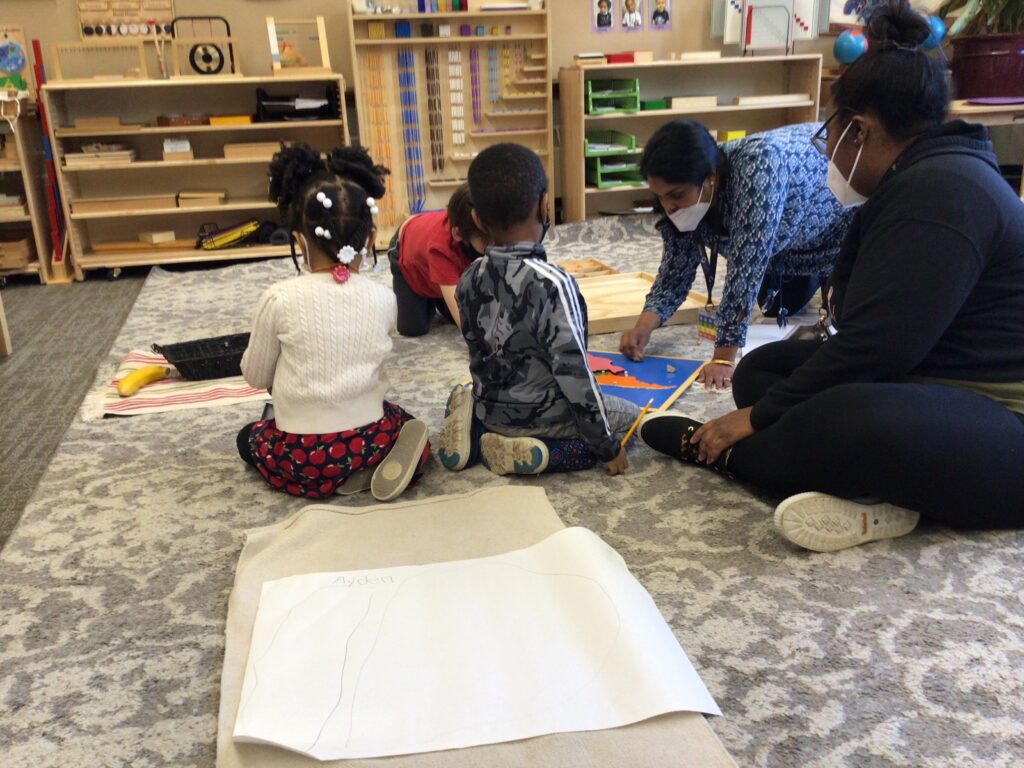

Order is the primary influence on student self-management of the 3-hour work cycle. Dr. Montessori’s discoveries about focus and psychic development are the keys to a work cycle that unlocks the child’s potential. It’s not difficult to create an environment that establishes this order. It takes awareness of the students, an intention to implement a routine, consistent observation to determine how the routines are working (or not), and a commitment to stay with it until the routines and culture of the classroom are established. One must exercise prudence and patience throughout the process. It won’t happen overnight and even once established, can slip unexpectedly into something chaotic for no “apparent” reason.

In chapter III of The Advanced Montessori Method- I, Dr. Montessori writes about her contribution to experimental science. It’s a lot to read and I know you’re busy…so here’s a suggestion to try:

Create an order to the daily schedule and watch how it works

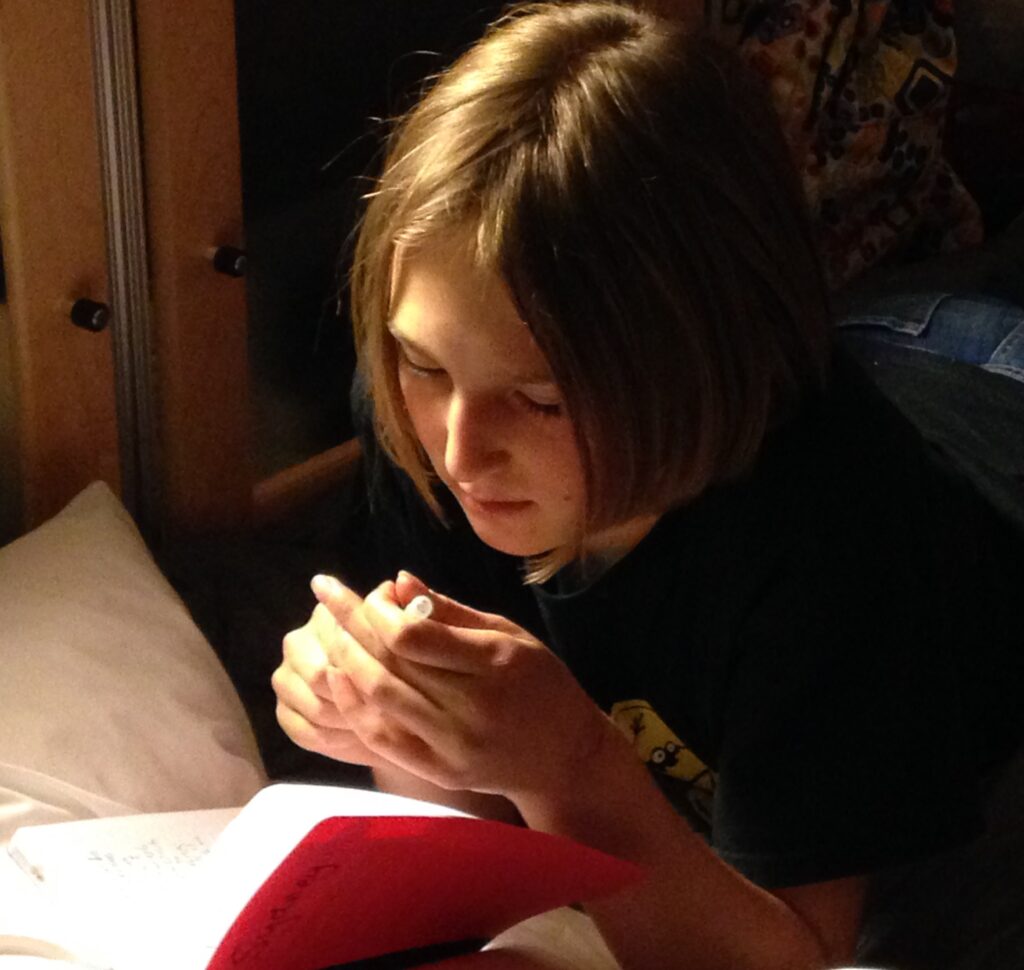

- Teach children how to start the day in quiet. My class had a choice of silent reading or sketching. “Teaching” meant to provide the materials (a choice book and a sketch book) and hold them accountable to the quiet by being quiet myself. I didn’t call to children who were talking, I quietly walked to them and gently touched them on the shoulder and put my finger to my lips indicating quiet. Try to remember that the social elementary child will not necessarily start their day this way naturally, so be patient as you stay firm. NOTE: On pages 75 to 85 Dr. Montessori writes about the activity cycle that takes place during the 3-hour work cycle for a variety of student personalities. EVERY one of them starts in quiet.

- Create the next part of the day that works best for you or your students. Many teachers like to bring the class together for a short class meeting (15 minutes or less!) to review the upcoming events and expectations of the day. Teach the students how to lead this meeting using a consistent agenda that is easy to follow. You can have a part to play: “Teacher Time” can be an item on the agenda for you to make announcements, give a mini lesson, or share a technique for managing a current classroom concern. (You could also have Current Classroom Concern as an agenda item: a time when students can bring up something they need to discuss.)

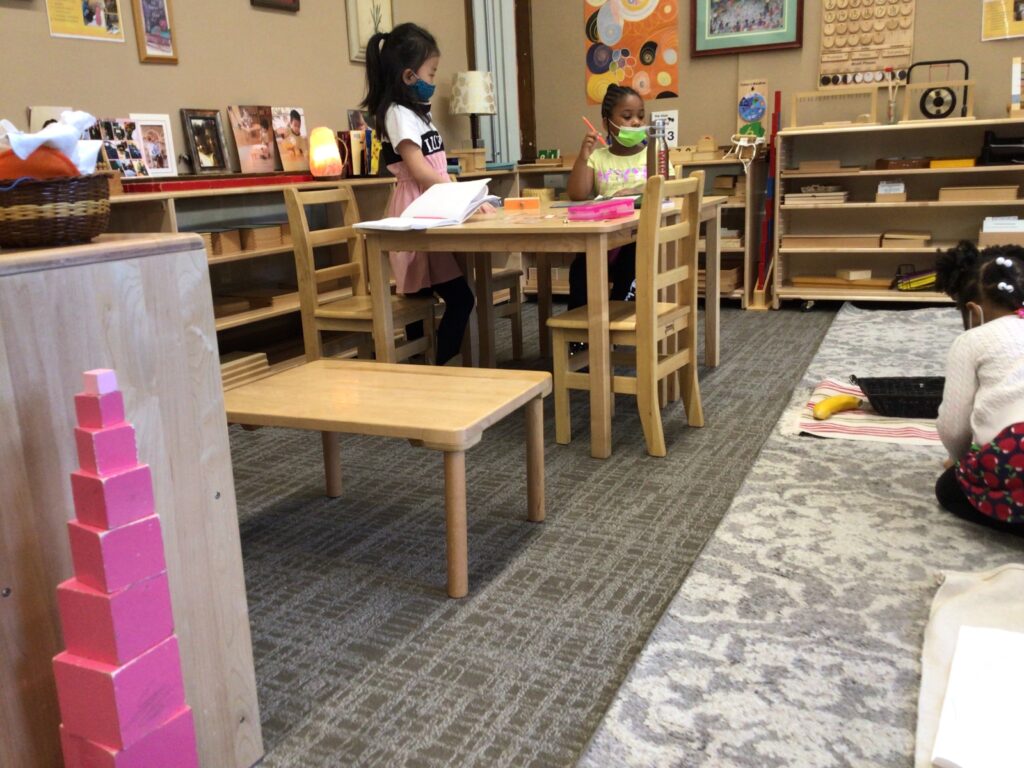

- Plan lesson times for minimal interruption to student work. I liked to get a lesson in right after a class meeting, so those students had a single lesson and then no further interruptions to their morning. I planned another lesson midway through the morning for those students who could manage their time well enough to get something done before and after, or I made the lesson for those students who had trouble returning to work after false fatigue. For those students, I would make sure the lesson was lively with a compelling follow-up opportunity that they would be dying to do. This helped them get into that second, deeper-focused work period. I’d plan a third lesson for the end of the morning so that students went to the midday routine after. Once the classroom was more “normalized” to the 3-hour work cycle and students could manage their time and tasks fairly well, I might add in an additional lesson or two, but that didn’t usually happen until later in the year…and some years, not at all!

- Keep myself quiet in voice, conversation, movement, and activity throughout the morning. Be a “guide on the side”, available for student questions, needs, etc. Don’t plan too much to do so that you can be available to your students while you teach the “3 Before Me” guideline*.

- End the morning at the same time and with the same routine every day. Teach the children where and how to put their work away for later, how to clear and clean tables, how to tidy shelves, how to clean up anything that is on the floor, and how to come to the circle when their responsibilities are complete. Spend a few minutes in the circle visually checking through the prepared environment to make sure the jobs are done. If they aren’t, make sure they are done before moving into the next part of the day…usually a lunch and recess routine.

Always take notes throughout the period of establishing these routines. Observation is the heart of our method! Give every new procedure some time to take root, then watch the impact before deciding something is or isn’t working or the students or yourself.

*3 Before Me: Ask Yourself (Can I answer this question or solve this on my own?), Ask a friend (Have you done this work? Can you help me figure it out?), Ask a person you don’t know…maybe someone older. (Have you done this work? Can you help me figure it out?) FYI: this one can be the hardest path to take, so giving students an opportunity to role play it in class meeting is a GREAT plan for support.