“I give very few lessons on how to give lessons…”

Maria Montessori, as quoted in Maria Montessori: Her Life and Work, by E.M. Standing © 1957 (pg. 307)

Did you know that the 3-Period lesson, a hallmark of Montessori methodology, was not “invented” by Montessori at all? That credit goes to the 19th century psychiatrist, Edouard Séguin, whose work was deeply studied by Maria during the years that she practiced medicine throughout the asylums of Rome.1 Nonetheless, the 3-period lesson, with its limited language and concentrated intentions (“naming”, “recognizing”, “pronouncing”) has become one of the pillars of Montessori lesson presentation. Especially in the primary or class for 3-to-6-year-olds in which language development is so great a focus, these uncluttered lessons are the key to growing a rich vocabulary that introduces and connects the child to a wide array of items and concepts.

Is the 3-period lesson relevant in Elementary?

Certainly, there is continued vocabulary development with elementary students, but this child has a different demeanor than the one found in the primary classroom. The elementary child’s thoughts are filled with questions, imagination is at its height, and constant chatter is their way of processing while being social.

For this little human who’s entered a new level of development, the simple 3-period lesson as was given in the primary class may be uninspiring, tedious, or even a complete turn-off. This child now requires lessons to provide a sense of wonder, piqued curiosity, and the thrill of opportunity to discover beyond the lesson. As Dr. Montessori said in the rest of that quote, the guide who wants to avoid creating obstacles to learning, needs to orient to the student before them.

The Elementary First Period

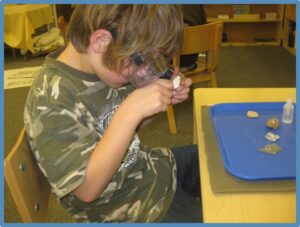

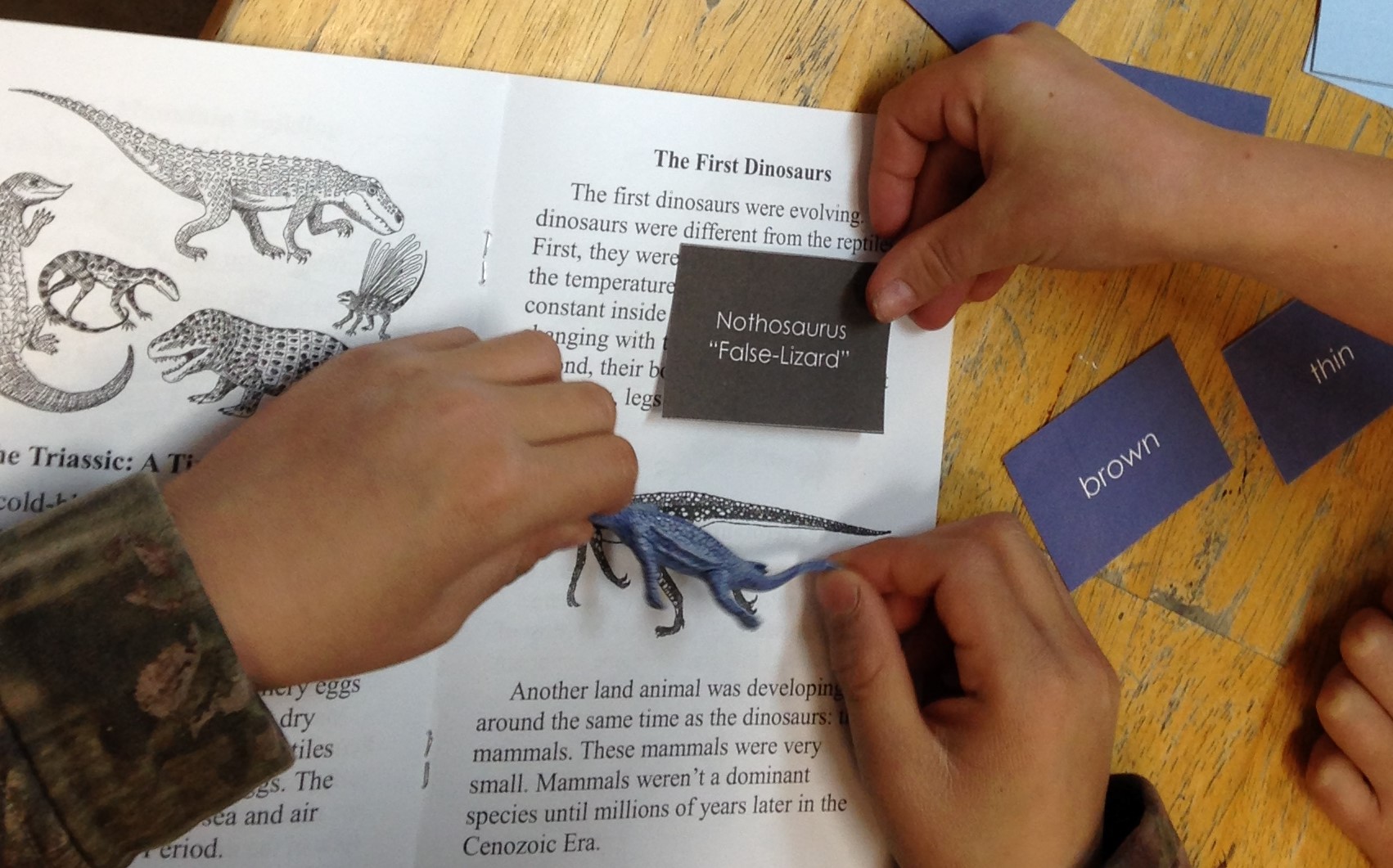

For the elementary student, the first period lesson needs to strike the imagination and touch the deepest inquisitiveness that lies within each child. My trainer, Biff Maier, called this initial, first period presentation for elementary “The Gift.”

Think about how one prepares a gift for giving. First, we choose something intended to delight the receiver. We anticipate the reaction and begin to plan for the moment of giving. We wrap the gift in an enticing way that will encourage eagerness for the discovery of the hidden treasure inside. And finally, we present the gift at just the right moment for it to be received with great enthusiasm.

Imagine preparing each lesson with this sort of attention: a lesson that will promote wonder and eagerness to know more.

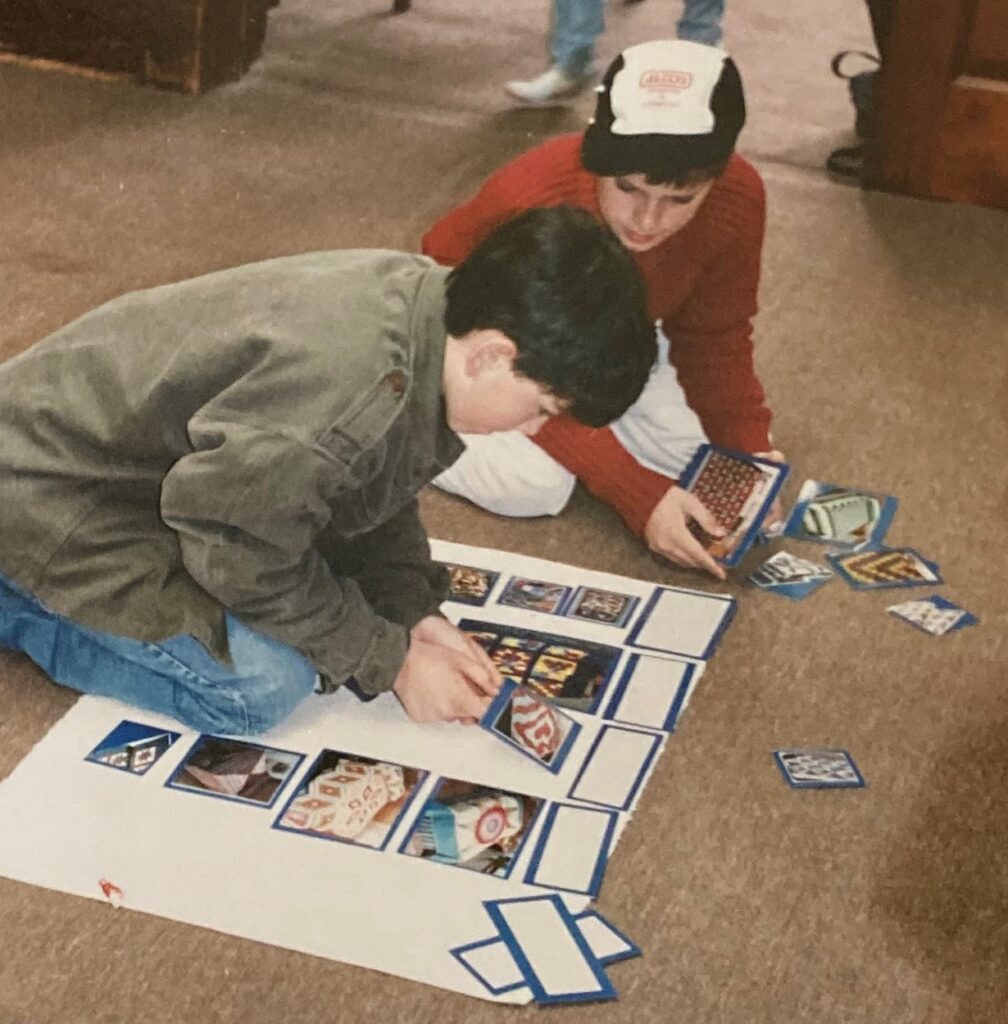

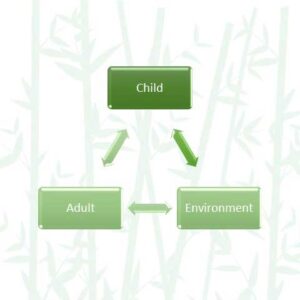

Second Period: Practice

If our First Period “Gift” has been received as hoped, our elementary students are off and running with the aid of the Human Tendencies. Exploration, Manipulation, and Activity spur the elementary students’ choices as they move forward throughout the rehearsal period. Their desire to become masterful is supported through Repetition and Exactness. All these tendencies guide the student’s efforts to master the intention of that inspiring first period gift.

As guides, we must be mindful to match the rehearsal phase, second period, to the student’s abilities so they can experience just the right amount of challenge to hold their interest, to give them consistent success and to keep their desire for more knowledge intact. This is flow2 at its best!

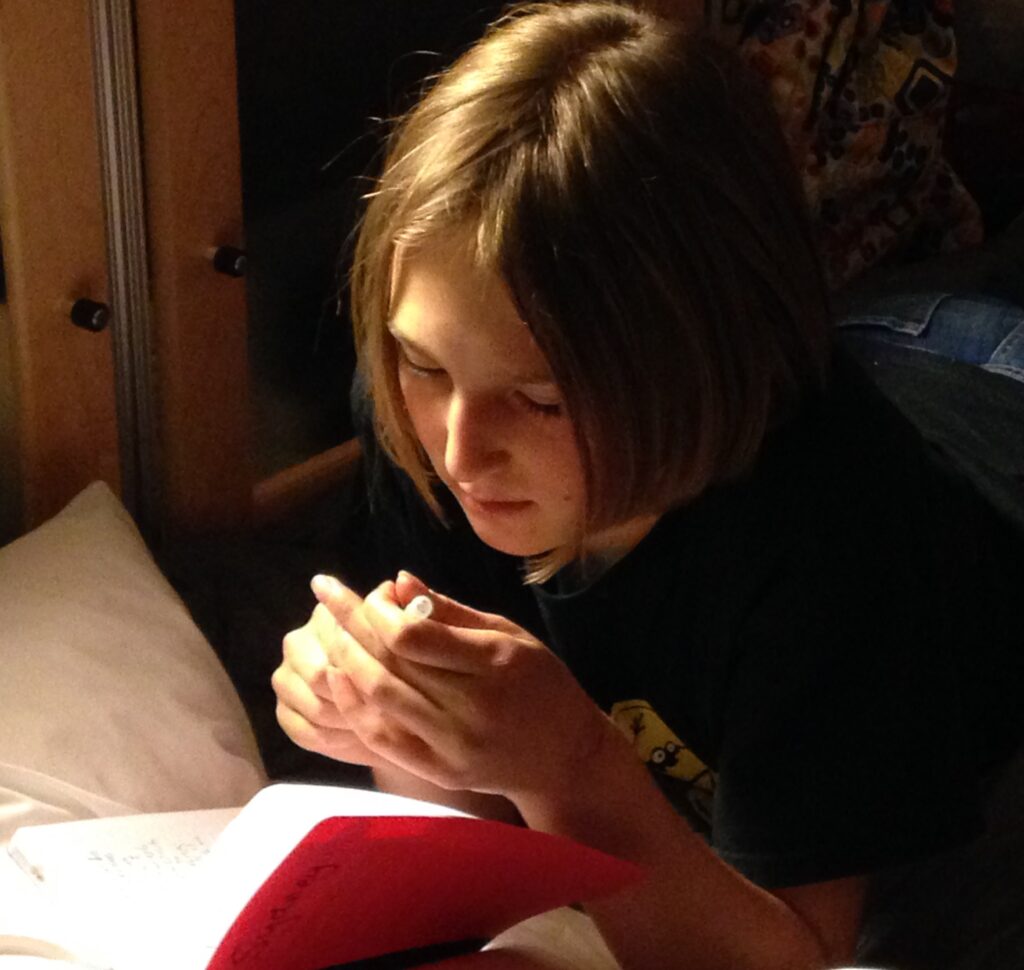

Third Period: Demonstration of Learning

Not that we could limit it, but all that talking and socializing that takes place in elementary is part of period #3. In their conversations, students say what they think, tell what they know, and continue the learning into new stages of mastery. Ever listened in on two 7-year-olds discussing their pets? They tell each other all sorts of “factual” data, as they instruct the other in the ways of their favorite furry beast. This could extend their knowledge of body parts and functions, behavioral inclinations, and environmental preferences.

Elementary children demonstrate their learning most comfortably through talking. Learning to share their learning through verbal presentations is the prelude to written and so on. There are countless ways to demonstrate learning…take a look at Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences Theory for ideas…but talking may be the one that is most natural for our elementary learners. So I encourage you to teach your students how to talk in ways that enhance their growing sense of mastery.

Cosmic Education: The Perfect Framework for Three-Period Lessons

The big ideas found in our Universe provide the best opportunities for creating the first period “Gifts” that lead to all the skill-building and engagement we could hope to provide our students. From science to history to humanity, the package that is Cosmic Education can offer the Montessori guide limitless lessons to inspire and engross the interests of our elementary students. When we follow the elementary version of the 3-period lesson, we don’t need a formula for giving a lesson. We simply need the sheer energy of providing the surprise and awesomeness of a gift.

1. You may read about this in Maria Montessori: A Biography by Rita Kramer, part 1: The Early Struggles, chapter 3

2. Flow, The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi © 1990, Harper Collins Publisher, New York, NY.